(Scroll down for the English version)

Para ver la foto con detalle, pincha sobre la de debajo: se abrirá en mi cuenta de flickr.

¡Hola de nuevo!

Este año ha sido muy intenso para mí, y desafortunadamente me ha sido imposible escribir siquiera una pequeña entrada en el blog. Dentro de no mucho dedicaré una entrada a lo que me ha mantenido tan ocupado, geológicamente hablando.

Hace un mes tuve la increíble suerte de asistir a un congreso geológico en Inverness, Escocia. Lo mejor de todo es que durante esa semana dedicamos un total de 5 días (5 de 8) a salir al campo y ver rocas bonitas, bien viejas y deformadas. Históricamente Escocia, y en particular el lugar por donde nos movimos, ha constituido una región fundamental para el desarrollo de la geología tal y como la conocemos hoy. Durante la segunda mitad del s. XIX, numerosos geólogos anduvieron por las tierras altas escocesas noroccidentales (NW Highlands), donde una combinación de ingenio y ejemplos de primer orden mundial permitieron que sus observaciones resultaran claves para el desarrollo de esta ciencia.

Un grupo de geólogos felices de ver rocas en el Lago Eriboll (¡incluido yo a la izquierda!)

Y digo combinación de ingenio y buenos ejemplos porque las dos cosas son necesarias en geología. Por mucho que alguien tenga habilidades especiales para observar y entender las rocas, si no se encuentra con algo interesante todo su ingenio se perderá en vano. Por ejemplo, sólo si el cielo está despejado durante un eclipse podemos preguntarnos qué sucede: si no fuésemos capaces de verlo no seríamos capaces de imaginar que algo así pueda ocurrir. Pues algo así sucedió en Escocia: ni una nube.

Todo empezó en 1855. Roderick Murchison, Director General del Servicio Geológico Británico, y James Nicol, profesor de Historia Natural en Aberdeen, visitaron juntos por primera vez el área para estudiar sus rocas. A lo largo de los siguientes años, ambos continuaron estudiando la zona por separado, y llegaron a ideas opuestas. Tan opuestas eran que el enfrentamiento científico llegó a lo personal, y recibió el nombre de la Controversia de las Highlands, con mayúsculas y todo. Murchison, así como su pupilo Archibald Geikie, consideraba que el norte de Escocia estaba formado por rocas dispuestas de forma continua, sin nada que las hubiese alterado. Hacia el oeste, rocas metamórficas del Arcaico (con más de 2500 millones de años de antiguedad) y hacia el este, rocas sedimentarias del Devónico (de unos 420 Ma). Nada raro, rocas jóvenes dispuestas sobre rocas viejas, como es habitual. Contrariamente, Nicols creía que había una falla que separaba las rocas del este de las rocas del oeste, y que la secuencia no era tan simple como Murchison la veía. Su creencia estaba basada en el hecho de que en algunos puntos, rocas metamórficas de alto grado (gneises) aparecían sobre cuarcitas cámbricas, un hecho aparentemente ignorado por Murchison.

Caricatura de Murchison (izquierda) y Geikie (derecha) como Director y pupilo. Extraída de la web citada al final. Año y autor desconocidos.

En la época se celebró un debate para aclarar la situación y acercar posturas, con el objetivo de proseguir el estudio de la zona con un objetivo común. Sin embargo, el debate se les fue de las manos y durante su intervención, Nicols fue callado a gritos por Murchison y sus seguidores. Como Director del Servicio Geológico, las ideas de Murchison y Geikie prevalecieron, y durante varios años el debate se dio por concluido.

En los años 80 del mismo siglo, sin embargo, dos geólogos independientes decidieron estudiar la zona de nuevo. Charles Callaway estudió el área del Lago Glencoul, mientras Charles Lapworth se centró en el septentrional Lago Eriboll. Ambos publicaron por separado en 1883 sus descubrimientos, dando la razón a James Nicols, caído en desgracia y muerto en 1879. Los dos confirmaban en sus publicaciones que la secuencia de rocas estaba interrumpida por no una, sino varias fallas de bajo ángulo que repetían parte de la sucesión (llamadas overfaults por Lapworth, y hoy conocidas como cabalgamientos). La foto de hoy es una de las mejores localidades para observar el Cabalgamiento de Arnaboll, estudiado por Lapworth en esta época. Si quieres saber más sobre lo que es un cabalgamiento, te recomiendo esta entrada anterior del blog.

Mapa de situación del área descrita.

Algunos de los protagonistas de la historia.

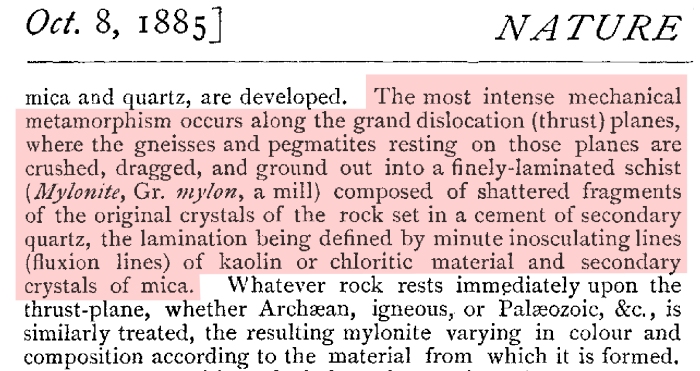

Justamente en el lugar que se observa en la foto, Charles Lapworth incluso describió un nuevo tipo de roca asociada a este cabalgamiento, caracterizada por una fina laminación. “El metamorfismo dinámico (deformación) más intenso ocurre a lo largo de los planos de cabalgamiento, donde gneises y pegmatitas del bloque superior aparecen machacadas, arrastradas y molidas hasta formar un esquisto finamente laminado (Milonita, del griego mylon, molino) formado por fragmentos desmenuzados de cristales de la roca original embebidos en un cemento de cuarzo secundario, donde la laminación está definida por capas continuas de caolinita (un tipo de arcilla), clorita (un tipo de mica) y cristales secundarios de mica”. Esta fue la descripción de Lapworth recogida en la revista Nature en 1885. Esta roca, hoy conocida efectivamente como milonita, se encuentra siempre asociada a zonas de alta deformación, en condiciones donde las rocas se comportan de forma dúctil, sin romperse. En este sentido, la definición dada por Lapworth sugiriendo una fracturación de la roca original no es exacta, pero las conclusiones que extrajo de su presencia (roca extremamente deformada) son más que acertadas.

Descripción original de las milonitas de Arnaboll por Lapworth en 1885.

Este tipo de roca, describió Lapworth en 1883, claramente sorprendido, “aparece por debajo del Ordovícico, por encima del Ordovícico, en medio de las cuarcitas (Cámbrico), encima de las cuarcitas (Cámbrico) y bajo gneises del Arcaico, ¡a la vez y al mismo tiempo!”. Esta fue la observación que le hizo pensar en fallas de bajo ángulo repitiendo la sucesión varias veces y de forma distinta en diferentes lugares.

Lapworth, sorprendido por lo que ve en 1883.

Archibald Geikie, nuevo Director de la Sociedad Geológica tras la muerte de Murchison, se enteró de las investigaciones de Lapworth y Callaway. Previendo el resurgimiento del antiguo debate que lo enfrentó junto con su tutor a Nicol veinte años antes, envió a dos de los mejores geólogos de la Sociedad con el fin de refutar los nuevos descubrimientos. Los dos, Ben Peach y John Horne, conocieron a Lapworth en el campo y seguramente intercambiaron opiniones e ideas. El caso es que lejos de contradecirlo, observando las rocas ambos quedaron convencidos con las interpretaciones de Lapworth, y así se lo comunicaron a Geikie. Acorralado por la evidencia, Geikie acabó cediendo un año después (1884) y enarbolando la teoría de cabalgamientos. Tanto fue así, que ese mismo año acuñó el término “cabalgamiento” en un artículo de la revista Nature, con pocas menciones a los verdaderos descubridores del fenómeno en Escocia: Nicol, Callaway y Lapworth.

Su descripción del cabalgamiento de Arnaboll es particularmente gráfica: “estas fallas son estrictamente inversas, pero poseen un ángulo tan bajo que las rocas en el bloque superior has sido empujadas horizontalmente hacia delante. La distancia que han recorrido es difícil de creer,…, al menos 16 km. … Uno casi se niega a aceptar que las rocas en la cima no están dispuestas normalmente sobre las rocas infrayacentes, sino que yacen sobre una falla prácticamente horizontal que las ha colocado encima. Masas de gneises del Arcaico han cabalgado sobre rocas más jóvenes y han sido empujadas largas distancias. Cuando un geólogo encuentra gneises sobre capas horizontales de cuarcitas con fósiles, lutitas y calizas, no es de extrañar que empiece a preguntarse si él mismo no estará de pie sobre su propia cabeza”.

Descripción original de un cabalgamiento por Geikie en 1884.

Las descripciones de cabalgamientos de Lapworth y Callaway en Escocia en 1883 fueron publicadas un año antes que las realizadas por Marcel Bertrand en los Alpes suizos en 1884. Si te interesa, puedes aprender más sobre una controversia similar mantenida por geólogos alpinos en años similares en este post antiguo.

En la foto se puede apreciar lo que todos describieron con asombro y estupefacción. En la base del cortado de 10 m aparecen unas rocas amarillentas bien estratificadas. Son cuarcitas del Cámbrico, con una edad aproximada de 500 Ma. En la parte superior aparecen unas rocas grisáceas sin una clara estructura interna. Son gneises del Arcaico, con una edad aproximada de 3000 Ma, unas de las rocas más antiguas de Europa. Rocas metamórficas de 3000 Ma encima de rocas sedimentarias de 500 Ma…algo no cuadra, ¿no? La clave está en la banda oscura que separa las dos. Un estudio detallado de esta roca oscura con la ayuda de un microscopio nos indicaría que se trata de las milonitas descritas por Lapworth. Por lo tanto, un cabalgamiento colocó los gneises sobre las cuarcitas. Prácticamente toda la deformación asociada a este desplazamiento, de varias decenas de kilómetros, se concentró en esta banda de milonitas, de apenas unos 30 cm de espesor. A un metro de la falla, ni los gneises ni las cuarcitas se enteraron del proceso, como quien dice: aparecen completamente indeformados.

En esta foto podéis ver un poco más de cerca las milonitas. Teniendo en cuenta que derivan de los gneises en la parte superior de la foto, el cambio experimentado es más que evidente.

Quien quiera visitar el Cabalgamiento de Arnaboll puede hacerlo en esta localidad. Ni que decir tiene que se trata de un lugar protegido y que cualquier daño al afloramiento es perseguido. No sólo el cabalgamiento, sino que toda el área es digna de una visita, ya que los paisajes son únicos e imponentes.

Si deseas conocer más sobre esta historia, te recomiendo el siguiente artículo, libro y web (en inglés todos):

- Butler, R. W. (2010). The Geological Structure of the North-West Highlands of Scotland–revisited: Peach et al. 100 years on. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 335 (1), 7-27.

- Oldroyd, D. R. 1990. The Highlands Controversy. Chicago University Press, Chicago.

- http://ontherocks.ie/2016/01/02/the-highlands-controversy/

In order to se the picture properly, click on the one below: it will be opened on my flickr account.

Hello again!

This year I have been very busy, and unfortunately it has been impossible for me to write even a small post for the blog. In a few weeks I will dedicate a post to the issue that has kept me so busy, geologically speaking.

One month ago I had the incredible luck of attending a geological conference in Inverness, Scotland. The best of it all was that we spent a total of 5 days (out of 8) in the field, and saw very nice, old and deformed rocks. From a historical point Scotland, and in particular the area we visited, has been a fundamental region for the development of the geological science as we know it today. In the second half of 19th century, numerous geologists walked through the NW Scottish Highlands, where a combination of ingenuity and world first-class examples caused their observations to be key in the development of this science.

A bunch of geologists happy to see nice rocks in the Loch Eriboll (including me on the far left!)

And I say combination of wit and good examples because the two things are necessary in geology. No matter how good are people’s abilities to observe and understand rocks, if they cannot apply them to the study of interesting cases, all their ingenuity will be lost in vain. For example, only if the sky is clear enough during an eclipse can we ask ourselves what is happening: if we were not able to see it, we would never imagine that something like that can happen. Well, something like that happened in Scotland: all possible interesting things were at sight there.

It all started in 1855. Roderick Murchison, General Director of the British Geological Survey, and James Nicol, Professor of Natural History in Aberdeen, visited the area together for the first time to study their rocks. Over the next years, both continued to study the area separately, and came to opposite interpretations. Their ideas were so radically different that the scientific confrontation became personal, and even received the name of the Highlands Controversy. Murchison, as well as his pupil Archibald Geikie, considered that the north of Scotland was constituted by rocks following a continuous succession, without any disturbance. It was very simple: to the west, metamorphic rocks of the Archean (with more than 2500 million years old) and to the east, sedimentary rocks of the Devonian (about 420 Ma). Nothing unusual, young rocks laying on top of old rocks. Contrarily, Nicols believed that there was a fault separating the eastern rocks from the western ones, and that the sequence was not as simple as Murchison described it. His belief was based on the fact that at some points, high-grade metamorphic rocks (gneisses) appeared overlying Cambrian quartzites, a fact apparently ignored by Murchison.

Caricature of Murchison (left) and Geikie (right) as Director and pupil. Taken from the webpage in the reference. Author and year unknown.

In the 1860s, a debate was held to clarify the situation and to reach an agreement, with the aim of continuing the study of the area with a common geological context. However, the debate went out of hand and during his speech, Nicols was shouted down by Murchison and his followers. Being the Director of the Geological Service, the ideas of Murchison and Geikie prevailed, and for several years the debate was settled.

In the 1880s, however, two independent geologists decided to study the area again. Charles Callaway studied the area of Loch Glencoul, while Charles Lapworth focused on the northern Loch Eriboll. Both published in 1883 their discoveries separately, and both agreed with the interpretations of James Nicol, who had fallen from grace and died in 1879. Both geologists confirmed in their publications that the sequence of rocks was cut not by one, but by several low angle faults that repeated part of the succession (termed overfaults by Lapworth, today known as thrusts). Today’s photo is one of the best locations to observe the Arnaboll Thrust, the field study area of Lapworth at the time. If you wish to learn more about thrusts, you can do so in this older post.

Map of the described area.

Some of the protagonists of the story.

In the very same spot observed in the picture, Charles Lapworth described a new type of rock associated to the thrust, characterized by a fine lamination. “The most intense mechanical metamorphism occurs along the grand dislocation (thrust) planes, where the gneisses and pegmatites resting on those planes are crushed, dragged, and ground out into a finely-laminated schist (Mylonite, Gr. mylon, a mill) composed of shattered fragments of the original crystals of the rock set in a cement of secondary quartz, the lamination being defined by minute inosculating lines (fluxion lines) of kaoin or chloritic material and secondary crystals of mica”. This was the description of Lapworth published in Nature in 1885. This rock, now well known as mylonite, is always associated with intervals which have undergone an intense deformation in ductile conditions, without breaking. In this sense, the definition given by Lapworth, which suggests a fracturation of the original rock, is not exact, but the conclusions drawn from its presence (an extremely deformed rock) were right indeed.

Original description of a mylonite by Lapworth in 1885.

These mylonites, described Lapworth in 1883 clearly surprised, “are below the Ordovician, above the Ordovician, in the Quartzite (Cambrian), above the Quartzite (Cambrian) and under Gneisses of the Archaic, all at one and the same time!” This was the observation that caused him to think of low-angle faults as the feature responsible for the multiple repetitions of the rock succession.

Lapworth, astounded with what he sees, in 1883.

Archibald Geikie, new Director of the Geological Survey after the death of Murchison, heard of the investigations of Lapworth and Callaway. Predicting an undesired resurgence of the old debate that had confronted him along with his tutor with Nicol twenty years earlier, he sent two of the Survey’s best geologists to refute the new discoveries. The two of them, Ben Peach and John Horne, encountered Lapworth in the field and surely exchanged opinions and ideas. The fact is that instead of contradicting him, by studying the same rocks both were convinced by the interpretations of Lapworth, and communicated their view to Geikie. Overwhelmed by the evidence, Geikie finally rejected his mentor’s view a year later (1884) and adhered to the thrusting theory. Moreover, the very same year he coined the “thrust” term in a paper published in Nature, without a proper acknowledging of the true discoverers of the phenomenon in Scotland, namely Nicol, Callaway and Lapworth.

His description of the Arnaboll Thrust in the locality of the picture is particularly graphic: “They are strictly reversed faults, but so low a hade that the rocks on their up-throuw side have been, as it were, pushed horizontally forward. The distance to which this horizontal displacement has reached is almost incredible, …, at least 10 miles (16 km). … One almost refuses to believe that the little outlier on the summit does not lie normally on the rocks below it, but on a nearly horizontal fault by which it has been moved into its place. Masses of Archean gneiss have been thus been thrust up through the younger rocks and pushed far over their edges. When a geologist finds verical beds of gneiss overlying gently inclined sheets of fossiliferous quartzite, shale, and limestone, he may be excused if he begins to wonder whether he himself is not really standing on his head.”

Original description of a thrust by Geikie in 1884.

The descriptions by Lapworth and Callaway of thrusts in Scotland in 1883 were published one year before than those in the Swiss Alps, described by Marcel Bertrand in 1884. You can learn more about a similar controversy among Alpine geologists at the time in this previous post.

In the picture you can see what these geologists described in amazement and awe. At the base of the 10 m cliff some well bedded yellowish rocks crop out. They are quartzites of the Cambrian, with an approximate age of 500 Ma. In the upper part gray rocks without a clear internal structure crop out. They are gneisses of the Archaean, with an approximate age of 3000 Ma: they are some of the oldest rocks in Europe. Metamorphic rocks of 3000 Ma on sedimentary rocks of 500 Ma… something does not feel quite right, does it? The key to solve this conundrum is the dark band that separates the two rock units. A detailed study of this dark rock with the help of a microscope would indicate that these are the highly sheared mylonites described by Lapworth. Therefore, a thrust must have placed the gneisses on top of the quartzites. All deformation associated with the displacement, of several tens of kilometers, was concentrated in this barely 30 cm-thick layer of mylonites. One meter away from the fault, neither the gneisses nor the quartzites seem to have noticed what was going on, as it were. They are totally undeformed.

In this other picture you can have a closer peek into the mylonites. Considering the fact that they were derived from the gneisses at the top of the photo, the experienced metamorphism is more than evident.

Whoever wants to visit the Arnaboll Thrust on its type locality can do so here. Obviously, the outcrop is a protected heritage and therefore any damage to it is strictly prohibited. The region is worth visiting, not only because of the thrust, but because of the scenery, unique and magnificent.

If you’re interested in the topic, I recommend you to read the following paper, book and webpage:

- Butler, R. W. (2010). The Geological Structure of the North-West Highlands of Scotland–revisited: Peach et al. 100 years on. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 335 (1), 7-27.

- Oldroyd, D. R. 1990. The Highlands Controversy. Chicago University Press, Chicago.

- http://ontherocks.ie/2016/01/02/the-highlands-controversy/

Un placer volver a sentir los pics geológicos, llegué a pensar que ya formaban parte de las “cosas de juventud”. Espero que tengas oportunidad de serenar un poco y vuelvas a contar cosas curiosas de las piedras que hay por ahí tiradas en cualquier parte.

Esta “entrada” te quedó muy elegante en cuanto a presentación, documentación, etc. La próxima más y mejor, te lo estás poniendo difícil

LikeLike